When a Manuscript Becomes a Book

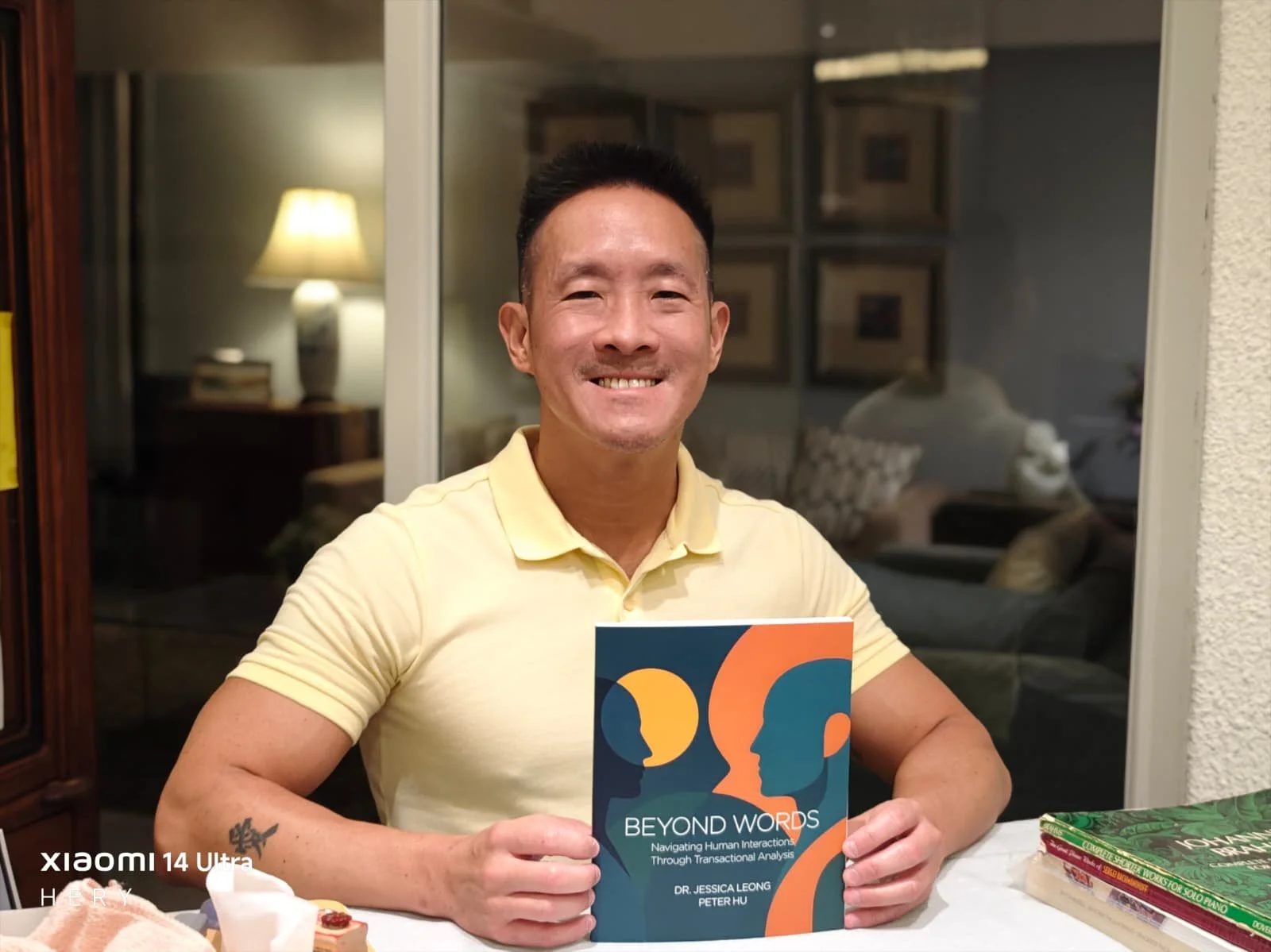

Photo by Hery Huangwei, captured on Xiaomi 13 Pro | Leica.

Today I picked up the first few hardcopies of a book I’ve had the privilege of co-authoring with Dr. Jessica Leong: Beyond Words: Navigating Human Interactions through Transactional Analysis.

Seeing it as an actual book – with a cover, pages, a spine that sits neatly on a shelf – feels surreal. For months, it had existed only as drafts, tracked changes, and long discussions. Now it has weight. You can drop it on a table. You can lend it to a friend.

People sometimes say that writing a book is like a long gestation, and that metaphor has stayed with me. This project kept asking me for a small share of each day – a bit of attention, a bit of emotional energy – often borrowed from other things I could have been doing. Over time, it was as if my life quietly redirected those small, unseen portions of itself toward the manuscript, until there was finally something tangible to hold.

Dr. Eric Berne, who founded Transactional Analysis (TA), once wrote:

“A patient is in treatment when his Child accepts the Adult of the therapist as a substitute for his own Parent. His Child abdicates his previous adaptations, in effect divorcing his Parent, and re-adapts himself to the therapist as perceived. In this phase he first perceives the therapist as a new, usually more permissive Parent, but one who can offer him the same magical protection as his own inner Parent, and that is the condition for the divorce.”

- Eric Berne, Clinical Notes ("In Treatment")

Berne is not arranging three tidy ego-state boxes here. He is trying to describe what it means for a person’s most exposed, childlike part to shift its loyalty from the harsh, inherited voices in their own head to the grounded, thoughtful presence of another human being.

Where Berne is tracing what happens when that vulnerable Child begins to trust a different Adult, Ursula Le Guin names what it looks like when that same Child is still alive inside an adult life. She once wrote that “the creative adult is the child who survived.” TA gives a very precise language for that survival: the ways our Child, Parent, and Adult states keep negotiating with one another inside ordinary life. At its best, TA doesn’t force people into new identities; it helps them recognise the arrangements they have already made, and consider whether those arrangements still make sense.

This book is our attempt to offer that kind of language in a way that is grounded, contemporary, and usable.

It is not the definitive word on TA, and it isn’t trying to be. It is simply one contribution – shaped by our particular histories, mentors, clients, and communities – to a much larger, evolving conversation about how humans relate, repair, and grow.