Understanding Jungian Psychological Types

Have you ever taken a personality test that told you you're an INFP, ESTJ, or something else—and thought, Now what?

Most typology resources stop at giving you a four-letter label. But Jung’s original idea of Psychological Types was never meant to put you in a box. It was meant to open a door.

Jung argued that people have different preferred ways of taking in the world (perceiving) and making decisions (judging). These preferences shape how we focus our attention and energy: for example, noticing concrete details vs. big-picture patterns, deciding through impersonal logic vs. personal values.

But John Beebe, in his book Energies and Patterns in Psychological Type, shows us that it's much richer than just picking your “top” preference.

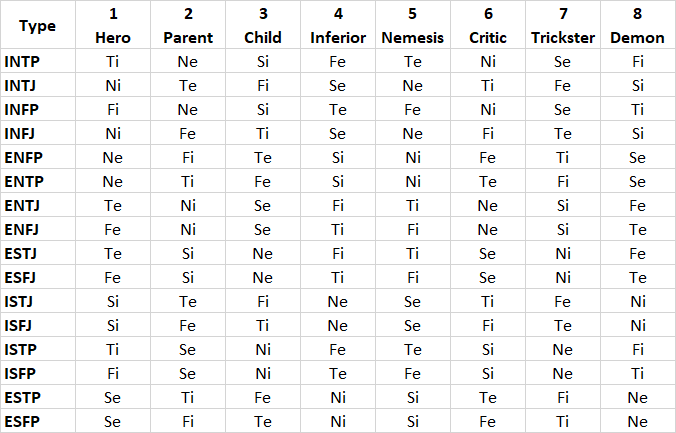

He describes your psyche as a cast of eight cognitive functions—each like an inner voice with its own role, strengths, and blind spots. Imagine your mind as a stage with different characters who step forward at different times, shaping how you see the world, solve problems, and respond to stress. That’s what the 8-function stack in the chart shows for each type.

Jungian Psychological Types – 8-Function Archetypal Stack

Instead of thinking of yourself as just an INTP or ENFJ, you can begin to recognize all these roles within you. For instance, if you’re an INTP, these are the eight voices you might notice:

Hero (Ti – Introverted Thinking): Your confident lead, the part of you that loves to analyze, dissect, and make sense of ideas with precision. This is where you feel most natural and sure of yourself.

Parent (Ne – Extraverted Intuition): The supportive guide in you that offers new perspectives, playful brainstorming, and helps others see possibilities they might have missed.

Child (Si – Introverted Sensing): The sensitive, cautious side that values familiar details and personal memories. It can feel safe and comforting, but also a little rigid or defensive when challenged.

Inferior (Fe – Extraverted Feeling): A vulnerable spot that wants harmony and connection with others, but can feel awkward or clumsy in emotional or social settings—especially under pressure.

Nemesis (Te – Extraverted Thinking): The defensive side that can dig in or push back with blunt logic when you feel threatened or dismissed.

Critic (Ni – Introverted Intuition): The skeptical inner voice that questions hidden meanings or long-term consequences, sometimes criticizing yourself or others for not seeing “the real truth.”

Trickster (Se – Extraverted Sensing): The part that scrambles rules and acts impulsively under stress, reacting to immediate sensory input in unpredictable ways.

Demon (Fi – Introverted Feeling): The deep shadow holding buried personal values and moral judgments that can sabotage you if ignored—but also carries potential for real, transformative self-understanding if faced.

Understanding these eight voices helps you see yourself more fully—not just your strengths, but also the parts that can trip you up or cry out for attention. It’s like getting to know the whole cast inside you, so you can work with them, rather than being surprised when they take the stage.

✅ You might see why you’re so precise in thinking but struggle to read the emotional tone in a room.

✅ You might realize your stress reactions aren't random, but the work of a neglected function trying to protect you.

✅ You can develop underused functions deliberately, rounding out your personality.

Beebe’s model is a roadmap to your whole self, not just your comfort zone. It’s not about limiting who you are—it’s about understanding the energies and patterns that drive you.

If you want to move beyond labels and really explore the inner cast of your mind, I’d love to help.

Curious about discovering your full type pattern? Reach out to me and let’s start the journey together.

Reference

Beebe, J. (2017). Energies and patterns in psychological type: The reservoir of consciousness. Routledge.